The Great Migration sees the united circular movement of around 1.5 million hoofed animals.

The primary participants are blue wildebeests (around one million), but there are also huge numbers of zebras as well as elands, impalas and gazelles.

At the heart of the Great Migration are the one million blue wildebeests

Then, in addition to the 1.5 million migratory animals, there are also predators like lions, cheetahs and hyenas in the mix, because many follow the migrating herds to hunt for prey.

Furthermore, hungry Nile crocodiles look forward to the herds crossing their rivers as they offer the chance of a meal.

The Great Migration is a far-reaching ecosystem that’s full of drama and spectacle.

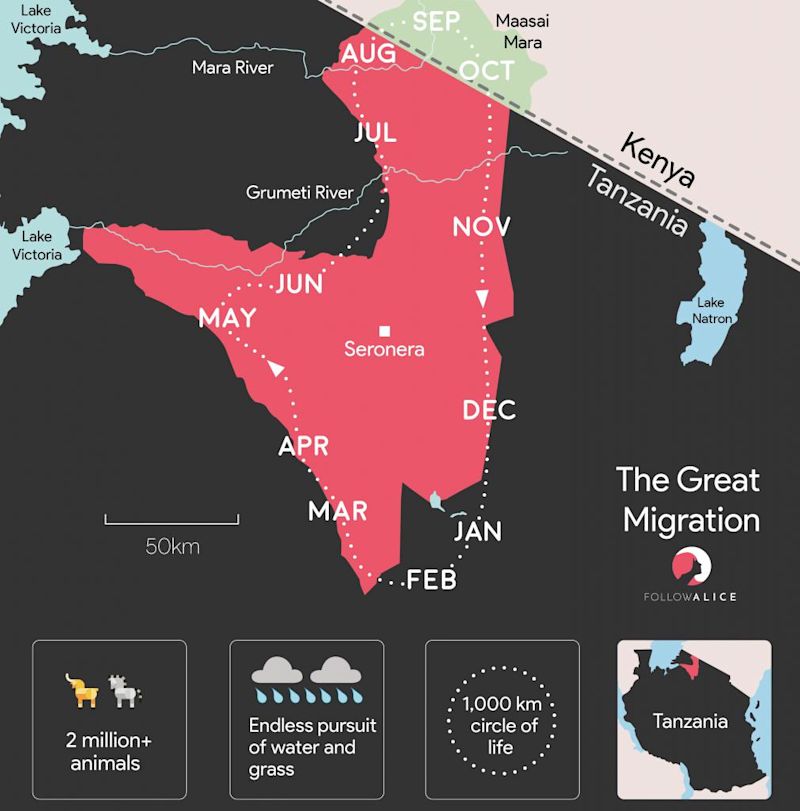

Map showing the general course charted by the herds of the Great Migration

Most of the Great Migration takes place within Serengeti National Park in northern Tanzania. But there's also overspill into Ngorongoro Conservation Area to the south, as well as Maasai Mara National Reserve to the north in Kenya.

While there’s so much that’s fascinating about the migration, what we want to share with you here are seven little-known facts about it. And they are fabulous, dinner-conversation facts to boot!

We're pretty sure fact #5 will blow your mind ...

A caveat: if you know almost nothing about this unparalleled migration, we recommend first reading our post Great Wildlife Migration (#Migration101). After that, come back here and join the Great Migration masters class!

Some blue wildebeests up close, so you have a good idea what animal we're talking about here

Blue wildebeests aren't, of course, blue. But there's a silvery–blue sheen to their coat when seen at certain angles in the light.

1. Wildebeests rely on zebras for their survival

The animals that make up the Great Migration are grazers. The very reason for their non-stop migration is the search for green pastures.

A herd of blue wildebeests in the Serengeti

The wildebeests of the Great Migration are fussy eaters. They only eat the shoots of grass.

Zebras, on the other hand, aren't picky. They eat the fresh, long grass, and in so doing, 'mow it down'. The wildebeests can then come in and access the shorter grass they need to survive.

So the roughly 200,000 zebras that travel harmoniously alongside the wildebeests of the Great Migration essentially enable the survival of the latter.

The zebras and wildebeests of the migration enjoy a peaceful coexistence

2. Nile crocs can survive on one or two feedings a year

Every year in the long dry season the herds of the Great Migration must cross some rivers like the Grumeti and Mara Rivers to follow their course northwards towards greener grass.

These river crossings are perilous occasions for a few reasons, perhaps most notably because of the hungry presence of Nile crocodiles.

Nile crocs can weigh up to 750 kg (holy smokes!). And the crocs of the Grumeti are some of the biggest in Africa.

Crocodiles can sleep with their mouths open

You would think such large beasts would need to eat constantly to survive. Yet, amazingly, some of the larger crocs can sustain themselves on just one or two wildebeest feeds per year! They gorge themselves, and then go into semi hibernation. They actually slow their heart rate and metabolism during this period. Amazing.

Did you know that Nile crocodiles live, on average, for 70 to 100 years??

Wildebeests crossing the Mara River – a dangerous past-time

3. Around half a million calves are born in two months

Roughly 400,000 wildebeest calves are born every year between January and early March in the southeastern plains of the Serengeti.

It's also a general calving season, as zebras and antelopes also give birth to young during this period. For many, this is considered the best time to visit the Serengeti, as it's exciting to see the newborn animals.

An adorable zebra foal

The dangers of the Great Migration to its participants cannot be overstated. The wildebeests, zebras and antelopes must confront thirst, hunger, exhaustion and predators. Predators include lions, leopards, cheetahs, African wild dogs, spotted hyenas and crocodiles.

A mother wildebeest suckling her newborn

The most vulnerable members of the Great Migration herds include, of course, the young. Only one in three calves will make it back alive in a year to the Serengeti's southeastern plains. So the continuation of the Great Migration is, in a sense, a numbers game.

Wildebeests have one of the highest fertilisation success rates of all mammals.

4. Calves are able to stand minutes after birth

Wildebeest and zebra calves are amazing. They quickly stand after birth, and soon thereafter can start running. In fact, wildebeest calves can walk on their own within minutes of being born. And within days they can keep up with the herd and even outrun a lioness! Zebra foals can also pretty much walk and even run after an hour.

Zebra foals begin to run about an hour after birth!

We call species like this precocial, meaning their young are born in an advanced state. The hoofed animals of the Great Migration are precocial to help them survive. They live with lions, leopards and other predators lurking around, watching, so if their young were unable to move, they'd literally be sitting targets.

Precocial babies need long gestation periods, since the foetuses must grow to greater maturity in utero. The gestation period of wildebeests and elands is nine months. For zebras, it's 13 months!

A wildebeest foal in Ngorongoro Crater

5. Adult lions can eat 40 kg of wildebeest in a sitting!

Lions don't eat all the time, but when they do, they go for it! Lions usually eat every three to four days, averaging around 6 kg a feed. But they can go for longer than that – even for a week or so.

This lion is looking lean and in need of a feast ...

After a long spell without food, lions go big. In fact, a fully grown male lion can chomp down on 40 kg (88 lb) of wildebeest in one sitting. That's about a quarter of its own weight!

After a really big meal, a lion can sleep for up to 24 hours. Cats, right?

A lioness digging in and showing off her gnarly gnashers!

Finally, we just want to point out that if you're really keen to see lions in the wild, the Great Migration parks of Serengeti, Maasai Mara and Ngorongoro Crater are among Africa's best national parks for seeing lions.

6. Wildebeest hooves leave a scent trail for others to follow

The Great Migration doesn't consist of one, solid herd. Rather, there's a main herd and satellite herds, all of which endlessly morph, splinter and coalesce over time.

The herd is at its most cohesive from late December to early March, when all the wildebeests (and other hoofed participants) gather together in the Serengeti's southeastern grasslands. This is calving season, a vulnerable time, and they're seeking protection in numbers from the ever-prowling predators.

Now you'll never look at hoofs the same way ...

When the animals are back on the move, however, the herd splinters and the animals spread out. This is especially the case when there's plenty of green grass.

New evidence suggests that the glands in the wildebeests' hooves secrete pheromones and faeces that stays on the ground. This allows their fellow wildebeests to follow their smell. And so the disparate herds can stay connected and link up. WOW.

The more you learn about wildebeests, the more you realise what phenomenal creatures they are!

7. The grunt of each wildebeest is unique

One of the other names for a wildebeest is gnu. The g is silent, so it's basically pronounced 'nu'. This is an onomatopoeic word for the grunting sound the animals make.

Similar to snowflakes, each wildebeest's grunt is unique. Mind-blowing stuff.

Something that's truly astounding is that each wildebeest has a unique grunt – a unique nu, if you will.

These grunts are important because they help the creatures to locate to one another. So when it's dark, or there's a large herd, a mother and foal, for instance, can find one another by listening for their unique nu's.

Thousands of wildebeests dotting the Serengeti plains – you can just imagine how helpful a unique grunting call can be!

And that's it. We hope you feel suitably fascinated!

To end, here's a video with our top tips for an incredible Serengeti safari!